|

| Johnstone Shire Hall 1950s (John Oxley Library) |

|

|

The Johnstone Shire Hall is a substantial inter-war building which illustrates the unprecedented

era of prosperity accompanying the expansion of the sugar industry in the Burdekin region. |

|

|

The Johnstone Shire Hall, constructed 1935-38, is significant as a good and intact example

of regional public buildings with Art Deco detailing, featuring locally inspired motifs. The Shire Hall is significant as

a building designed by the architectural partnership of Hill and Taylor, prominent local architects in North Queensland between

the first and second World Wars. |

|

|

The building is an important element of the Rankin Street streetscape. |

|

|

It has significance to the local community as the civic centre of Innisfail. |

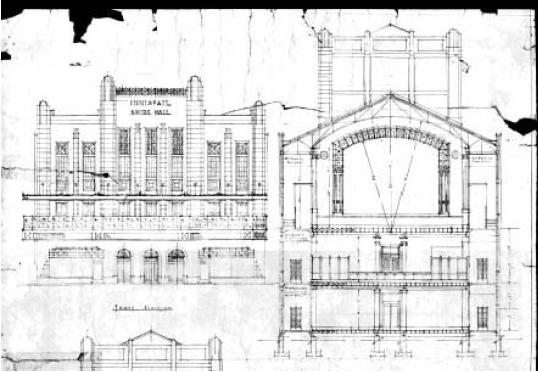

| Johnstone Shire Hall Original Drawings |

|

| kept in Council archive (JSC) |

INTRODUCTION

The study has been carried out by Richard Allom

and Desley Campbell-Stewart of Allom Lovell Architects and by Helen Lucas consultant historian (2008)

SUMMARY

OF FINDINGS

The study finds that the Johnstone Shire Hall is not only

a significant building in North Queensland by architects Hill and Taylor but one which reflects the particular era and circumstances

in which it was conceived and built – the wealth and optimism of the town, the economic depression of the 1930s and

the determination of the State Labor government to see substantial public buildings constructed throughout Queensland.

The building is also significant as part of a suite of

‘cyclone proof’ concrete buildings constructed in Innisfail in the 1920s and 1930s for its iconic status as part

of the townscape and for its long association with the political and social life of the region.

The building is in good condition but is lacking in amenity

in some aspects including wet areas and less than optimum floor space in the foyers to the hall and Council offices. Indeed

it also fails in some respects to meet current building codes.

The conservation of the Johnstone Shire Hall will require

then not only the care of early building fabric but to ensure the continued use of the building as the centre of political

and community life.

Policies to achieve that objective forming part of the

present document must be matched by clear vision and a strategic view to see that vision brought to life.

HISTORY

The Johnstone Shire Hall is part of the history and culture

of North Queensland. It represents a range of themes and events centred on Innisfail that came together in the 1930s.

EXPLORATION AND EARLY SETTLEMENT

In the 1860s the most northern colonial settlements

in Australia were Cardwell, which was established in 1864 and Somerset, established on the tip of Cape York in 1863. Little

attention was paid to the Johnstone River region until early 1872 following the ship wreck of the brig Maria. On 25 January the Maria, carrying a party of gold miners from Sydney to New Guinea, was

wrecked on Bramble Reef 30 miles north of Cardwell. A few survivors managed to make it back to Cardwell to raise the alarm.

The search for other survivors, conducted by Captain Moresby of the HMS Basilisk, included a preliminary

survey of what is now known as the Johnstone River. Records of this early survey prompted Sub-inspector Robert Johnstone to

explore the region in 1873 as he was passing on a return trip from Green Island to Cardwell. He spent a day examining the

river and found it "one of the noblest rivers in Australasia".1

However it was the discovery of gold on the Palmer River

that provided the impetus for the Queensland Government to conduct a more thorough search of the northern coastline in an

attempt to find a suitable port to service the new gold field. In 1873 George Elphinstone Dalrymple was instructed by the

government to explore all rivers and inlets between Cardwell and the Endeavour River, and to ascertain the suitability of

the surrounding soil for agricultural purposes and finally, to collect botanical specimens.2

On 4 October 1873 Dalrymple arrived at the river noted

by Robert Johnstone. He named the river after Johnstone because "he first brought to light the real character and value of

this fine river and its rich agricultural land".3

While charting the river system Dalrymple undertook a detailed

investigation of the Johnstone River, the South Johnstone River and adjacent countryside. He found a coastal basin which was

suited to agriculture and sugar growing and a fine harbour and river estuary. While the ports of Cooktown (1873) and Port

Douglas (1877) were being established to provide access to the goldfields of the Palmer River and the Hodgkinson Goldfield

it was the red gold of cedar which drew the timber cutters to the Johnstone River region. From 1874 cedar getters from Cardwell

were working the area between the Johnstone and Tully Rivers. By 1880 much of the best cedar had been cut and the timber cutters

were moving out of the area to the Atherton Tablelands. They were leaving as the first permanent European settlers were arriving.4

ESTABLISHMENT

OF SUGAR PLANTATIONS

The first settlers in the region were Leopold Stamp

and Heinrich Scheu. Leopold Stamp, a timber cutter, took up residence with his family on 4 March 1880 and Scheu, with his

family in May 1880. However, the man honoured with establishing the first European settlement in the region was Thomas Henry

Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald was one of the earliest sugar men in the Mackay district, however, when rust ruined the 1874-75 crop

he was declared insolvent and lost his plantation. He turned to his profession of surveyor until, motivated by a rise in sugar

prices in the late 1870s, he set out to look for a suitable location for a new plantation. His investigations through the

north and far north of Queensland led Fitzgerald to the Johnstone River area.5 Fitzgerald, together with his backers, Bishop

Quinn, Catholic Bishop of Queensland, the Sisters of Mercy and Miss O’Reilly formed a company and applied for their

original selection on 2 February 1880. In June Fitzgerald & Company arrived at the Johnstone River and took up fifteen

blocks of land, each 1,280 acres of river frontage, in the vicinity of the present town. The blocks were taken up under the

terms of the Land Act of 1868 which limited the size of blocks for sugar plantations to between

300 to 1,280 acres.6

Work commenced on clearing the land and planting sugar

cane. All manual work was undertaken by Pacific Islanders. By 1881 the regions first mill was under construction. News that

Fitzgerald had built a mill created speculation and soon other independent selectors were moving into the area. New sugar

companies were formed and within four years another three mills were operating in the district and more land was under cultivation.7

This first phase of sugar production would set the foundation of the Innisfail district as one of Queensland’s pre-eminent

sugar producing regions.

ESTABLISHMENT

OF GERALDTON

As the district developed as a sugar producing region it

was inevitable that a small town would be established to support the burgeoning industry.

The first sale of town allotments occurred in October 1883.

This small town was initially known as Geraldton. Apparently at the time of the sale the land was still covered with scrub

and the streets merely lines on a surveyor’s plan. The town was situated on a series of three main hill formations with

ridges running roughly parallel to the river up to a summit at the corner of Owen and Grace Streets. Because many parts of

the town were inaccessible at the time of the first land sale, some buyers inadvertently bought land that was unsuitable for

their purposes. For instance, the Johnstone Divisional Board, proclaimed on 28 October 1881, purchased two allotments in Owen

Street just behind the present shire hall in Rankin Street. At the time the Divisional Board was unaware that the land formed

a large lagoon and was separated from Rankin Street by a precipice. Once aware of their mistake the Board negotiated the purchase

of the present allotments in Rankin Street where all four shire halls have since been located.8

Despite the Divisional Board locating its office

in Rankin Street, most of the town activity centred on the Esplanade. The Port of Geraldton was gazetted on 1 November 1887

as a Port of Entry and Clearance and a Warehousing Port under the Customs Act of 1873. A customs

house was built on the corner of Edith Street and the Esplanade (later the site for the Commonwealth Bank) with associated

buildings erected near the wharves. Apparently the early intent was for Rankin Street to be the main street, however, because

transportation at the time was via the river most of the activity centred on the Esplanade.9

In the early days of settlement timber was plentiful and

was an important resource. Many of the town’s early buildings were constructed using local timber that was pit sawn

on the banks of the Johnstone River. 10 Some of the early timber buildings erected in the town included the Post Office and

Post Master’s house which was constructed in Rankin Street. This street again became the preferred site of the main

street when the potential for flooding ruled out the Esplanade.11

By the turn of the century many things about Geraldton

had changed. Clearing of vegetation in the town continued as new buildings were erected. Businesses in the town included an

aerated waters factory, two bakers, a butcher and three new hotels; the Union, Exchange and the Imperial. The waterfront was

lined with wharves and a ferry was running across the South Johnstone River. A Chinese merchant banker and entrepreneur, Tam

Sie, had pulled down his old store and erected a new one on the adjoining site. Dairy and milking yards had been erected behind

the hospital and the School of Arts, overlooking the ferry site on the river, was opened in 1898. Despite these developments

the town roads and footpaths were unpaved and during heavy rain became impassable because of the deep mud.12

New timber and iron buildings were replacing some of the

older ones. The town was attracting more business despite the river being the only reliable access in and out. For instance

Mellick arrived in March 1902 and started his business in a small shop that had been built by Tam Sie. He built the first

reinforced concrete building in the town in Rankin Street in 1907. This building is still standing despite being damaged in

both in the 1918 cyclone and in Cyclone Larry in 2006. By 1909, the streets of Geraldton were lighted with oil lamps on posts.13

The town changed its name from Geraldton in 1910 after

a Russian ship, heading to Geraldton in Western Australia, arrived by mistake at Cardwell. A Shire meeting was held to choose

another name. The name Innisfail was chosen in honour of the early settler Thomas Henry Fitzgerald; as it was the name he

had called his mill and plantation on the banks of the Johnstone River.14

By the time Geraldton had changed its name to Innisfail

it was a prosperous place with numerous public and civic buildings. It offered support and commercial activity to the people

of the district and was looking to improve its streets and access with new bridges and upgraded roads.

1918 CYCLONE

Innisfail suffered a setback in its progress when it was

almost destroyed by a cyclone on 10 March 1918. At 7am the Astronomical Bureau in Brisbane advised that a cyclone was approaching

the coast between Cooktown and Bowen. "It appears to be dangerous" warned the Bureau. Throughout the day the wind strengthened

and by 4pm the Astronomical Bureau was warning that it was a dangerous cyclone which was moving south westwards towards Innisfail.

The eye of the cyclone passed directly over Innisfail between 9 and 10pm. The pressure of the cyclone was never measured but

it registered the lowest barometer measurement possible, 27.35 at 7pm. While the strength of the cyclone was not able to be

recorded it was reported to have had the second lowest reading for a cyclone ever known. Recorded wind gusts ranged from 150

to 180mph. After the eye of the storm passed the winds came back in the opposite direction and most buildings still standing

were destroyed by the force of the strong winds.15

As buildings were destroyed people sought shelter where

they could. Many crowded into the cellar of Nolan’s building in Rankin Street; some 200 hundred people also sought shelter

in the basement of Mellick’s store in Rankin Street and 400 people packed into the Shire Hall across the road. Dorothy

Jones said that every building in the town was destroyed or damaged.16 While Mellick’s and Nolan’s buildings were

damaged their partial survival allowed over 600 people to shelter from the cyclone. These two buildings were the only two

reasonably intact buildings standing after the cyclone and it was noted that they were constructed of reinforced concrete.

The destruction of the old town of Innisfail was an enormous

blow to the district which relied on the services the town provided. While the town started to rebuild itself it was not until

the 1920s that it was significantly reconstructed.

NEW

TOWN

Following the 1918 cyclone Innisfail was virtually rebuilt.

A large proportion of building owners chose reinforced concrete as the preferred material to replace their destroyed timber

buildings.17 This major rebuilding of the town took place predominately in the 1920s and 1930s.

During this twenty year period substantial and decorative

buildings were constructed displaying Interwar Modernist and Art Deco styles. Today, despite the impact of Cyclone Larry in

March 2006, these buildings, predominantly in Rankin and Edith Streets, form an unusually intact central business district.18

It was probably fortuitous that the Van Leeuwen brothers,

Wilhelm (Bill) and Peter, arrived in Innisfail around the time of the 1918 cyclone. The Van Leeuwen brothers were from a family

of builders in Baarn, Holland. Bill migrated to Brisbane and brought out his younger brother Peter just prior to World War

I. Because Bill had to be in Australia for five years before assisting his brother to migrate it is likely that he was here

by about 1909.19

The Van Leeuwen Brothers began building in Brisbane where

they were involved in a lot of construction work including houses in Susan Street, Red Hill and the National Bank. They also

worked on the Hardy Brother’s building in Brisbane where Peter also built the interior joinery. They were responsible

for a number of houses and large buildings in Longreach including a reinforced concrete hotel about 1923. 20

Wilma Erie [pronounced Erich], Peter Van Leeuwen’s

daughter, did not know why the brothers went to Innisfail but she said that after the 1918 cyclone they were "johnny on the

spot" because of their already significant amount of building work in Queensland and their preference for building in reinforced

concrete. Wilma has a photo of Bill sitting on rubble after the cyclone and the assumption has been that they were already

in the town during the cyclone. However, as happened after Cyclone Larry, which seriously damaged Innisfail in 2006, it is

possible that they went to the town to help with the reconstruction.21

During the next two decades Bill and Peter Van Leeuwen

built a large number of the major buildings in Innisfail including the Church of England, Commercial Banking Company of Sydney,

the Bank of New South Wales, the Commonwealth Bank, the Crown Hotel, the Innisfail Water Tower, the Grand Central Hotel, Queens

Hotel, the Reagent Theatre, Ambulance Station, the National Bank, a number of cement houses and a large number of timber houses.

The brothers set up teams of men to carry out the work. Most of these men were from northern Europe and they remained working

for Bill and Peter and later for Peter until the outbreak of World War II. Sadly, Bill Van Leeuwen was injured during the

construction of the Johnstone Shire Hall in May 1937 and he died on 3 November 1937. Peter, who took over supervision of construction

on the Johnstone Shire Hall, also continued working with his teams of men until most of the men were interned during the war.22

It is thought that Peter Van Leeuwen did some design work

but the brothers also worked with architects, particularly when building government buildings or banks. There is photographic

evidence that they were contractors on the National Bank in Cairns which was designed by Architects Hill and Taylor of Cairns.

The National Bank was constructed some years prior to their collaboration with Hill & Taylor on the Johnstone Shire Hall

in 1935.23

After Bill died in 1937 Peter continued with the supervision

of the work on the Shire Hall and managing the teams of men working on many projects in the district but, his daughter said,"

his heart was no longer in it". After his teams of men were interned, and mostly sent to work in the mines in Mount Isa during

the Second World War, Peter worked for the American Army in the Engineering Section in Townsville. After the war he worked

for Brisbane engineer, Jack Mulholland, a family friend, supervising the construction of a number of major projects including

the North Gregory Hotel in Winton, the Cardwell Water Supply, the Tully Mill, Innisfail Swimming Pool, Tully Hospital, LG

Hunter shops in Cairns and a large house in Gordonvale.24 Mulholland, who in 1933 was acting as a contract engineer to the

Johnstone Shire Council,25 is honoured as one of Queensland’s significant engineers who worked across Queensland designing

some of the state’s major buildings and industrial projects. He is particularly renowned as the engineer who designed

most of the significant buildings in Winton.

The Van Leeuwen Brothers and later Peter Van Leeuwen were

the most significant builders in north Queensland and quite possible in Queensland prior to and between the wars. Their influence

can be seen particularly in the post 1918 cyclone building boom in Innisfail and in the major public buildings in Innisfail

commissioned or financed by government during the 1930s Depression.

GOVERNMENT

INITIATIVES

However, while the Van Leeuwens provided teams of tradesmen

experienced in all types of construction but particularly in reinforced concrete other factors were influencing the ability

of the Shire Council, business and the community to rebuild Innisfail.

The Local Authorities Act 1902 abolished divisional boards and created city, town and shire councils. Under this act, Johnstone Divisional Board was

abolished and its functions were transferred to Johnstone Shire Council on 31 March 1903. Under the Local Authorities Act

1902, the primary function of Johnstone Shire Council was to provide health services, parks and reserves,

cemeteries, libraries and recreational facilities, street lighting, etc. Council also had powers in relation to the construction

of buildings, fire prevention, health issues, public nuisances, places of amusement, public carriers, slaughter houses, markets

and animals and traffic. These general powers were exercised through the passing of Council by-laws approved by the Governor

in Council.

The minutes of the Johnstone Shire Council meetings in

the 1910s and early 1920s reflect the Council’s powers and role under the 1902 Act. The Council Consultant Engineer,

Harding Frew of Brisbane, had prepared a draft town plan for Innisfail which basically devised a much needed drainage, street

formation and footpath program.26 By September 1921 the Council had opened a new Memorial Park and Rotunda27 and by November

1921 regulations had been introduced to control rats and mosquitoes. These regulations included directions that floors of

houses needed to be constructed 9 inches above the ground. Council also had the power to demolish houses if it was felt necessary.28

The Johnstone Shire Council clearly implemented its powers under the 1902 Act because, at a special meeting of council on

28 November 1921, a number of properties in China Town had been inspected and a list prepared for demolition.29

Significantly, after the destructive cyclone of March 1918

left only two concrete buildings standing in the business centre of Innisfail, the council had approved a new set of by-laws

on the 17 December 1924 which were approved by the Governor in Council on 6 June, 1925 governing the type of building which

could be constructed in the main part of the town.30 These By-laws governed the type of fire proof material to be used. This

created a construction environment that utilised reinforced concrete, the most appropriate and readily available material

at the time.

WEALTH

OF SUGAR

While the Council had introduced regulations and by-laws

under the 1902 Act the ability to rebuild Innisfail was dependent on the prosperity of the cane industry. At the time of the

1918 cyclone sugar cane growing had entered its second phase in Queensland. Large plantations with their own mills and South

Sea Islander labour was no longer used in the cane industry.31 From about 1916 cane was being grown on family farms using

gangs of labourers employed seasonally for cutting; with the cane crushed in large central mills. This transformation in the

industry was not brought about simply by market forces but by conscious government policy backed by legislative sanctions

and large economic incentives.32 The 1910 Royal Commission into the Sugar Industry recommended the construction of an 8,000

ton per season central mill at South Johnstone in 1914.33 Loan funding was supplied by the State to build, manage and maintain

the new mill. In 1916 the Commonwealth Government appointed a board of inquiry to report into the sugar industry in Australia,

to look at over supply and to investigate the need for further mills. The inquiry decided that there would not be need for

any further mills in the region before 1920, so the Innisfail district benefited from having the only mill in the area. A

second Royal Commission in 1919 recommended that the Commonwealth Government take control of the industry and increase the

price of sugar. By 1921, a good season, together with the improved price for sugar and the continuing markets in Britain and

Canada gave impetus to the industry. 34

AMENDMENTS TO THE LOCAL AUTHORITY

ACT AND NEW JOHNSTONE SHIRE COUNCIL BY-LAWS

The improvements in the sugarcane industry were reflected

in the rebuilding of Innisfail, where, despite the beginning of a world wide depression there was considerable public and

private construction. A number of reinforced concrete commercial buildings were constructed in Edith and Rankin Streets by

1922. However, by 1924 the Council advised that "…n view of the growing importance of this district that this council

supports the actions of the School of Arts Committee [in their request for a new School of Arts building]…s the present

one is not keeping up with the status of the town."35

These concerns about the quality of towns and their

buildings were reflected by the Queensland State Government, who in 1923 introduced the "first instalment in town planning

powers.36 Followed in March 1925 by amendments to the Local Authority Act 1902 – 1924 which

allowed the declaration of ‘First Class Areas’ under Clause 185 of the Act. Under this amendment councils were

"given control over construction materials and other aspects relevant to fire prevention…they] could regulate classes

of buildings that could be constructed…and could] stipulate the size of blocks and the height and alignment of buildings."37

As a result of their concern about the poor quality of

buildings being erected in the town, Johnstone Shire Council took advantage of the State Government’s legislative amendments

by writing to the Home secretary on 19 March 1925 requesting that the centre of Innisfail be declared a "First Class Area".

The Council applied to the Governor in Council to have

the "whole of Section iii, iv, v, xxii, together with that part of Section xiii comprising Lots 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 17,

18 & 19, also that part of Section xi comprising Lots 8 to 11 included in a First Class Area. The application, which was

for the centre of the town of Innisfail, was approved and published in the Government Gazette on 4 June 1925. The Council

advised that "this step has been taken by Council…s the town of Innisfail is progressing rapidly and a check needs putting

on the poor class of buildings that are inclined to be erected from time to time."38

The declaration of the centre of Innisfail as a ‘First

Class Area’ gave the Johnstone Shire Council "…ontrol over construction materials and other aspects of fire prevention…39

in buildings.

Following the declaration of the First Class Area, Council

resolved at its meeting on the 17 June 1925 "…hat all plans and specifications and applications for buildings in the

first class section be referred to the Council’s engineer for his report thereon," and at its meeting on 15 July 1925

"…hat in future all applications be advised that the Act must be strictly complied with."40 Following these declarations

a number of applications were received by Council during late 1925 and 1926 which were referred to the Council engineer requesting

that he "assess the applications against the provisions of the Act." 41

At the same time the Council requested that a new set of

By-laws be approved by the Governor in Council in accordance with Section 206 Clause 1 of the Local Authorities Acts 1902

– 1922. These By – laws, drafted by the previous Johnstone Shire Council were redrafted by the newly elected Johnstone

Shire Council Legislative Committee after a special meeting on 10 September 1924.42

Unfortunately, the By-laws drawn up by the Johnstone Shire

Council and approved by the Governor in Council on 4 June 1925, did not include a chapter giving details on the type of material

to be used in the construction of buildings in the city of Innisfail. There were twenty chapters in the new Johnstone Shire

By – laws dealing with a wide range of issues such as sewerage and drainage, spouts and gutters, public safety, theatres,

animals, cemeteries, noxious weeds, bathing houses, water and rates. These new Council By laws were extremely comprehensive

so it is surprising that there was no By- law published in the Government Gazette of 4 June 1925 giving details on the type

of building construction the Council would approve for the town of Innisfail.43

A further search of the Government Gazette during 1925

showed that local authorities across Queensland were introducing similar By – Laws to that of Johnstone Shire Council.

Tambo, Kingaroy and Rosewood all introduced new By –laws during 1925 and, as with Johnstone Shire, none of them had

a specific By-law dealing with the materials to be used in the construction of buildings. However, on 22 June 1925, Murgon

Council introduced By – laws which contained a By-law that said "every building…hall be enclosed within walls

constructed of brick, stone, concrete or other hard and fire resistant materials…44

While no evidence has been found in the Queensland Government

Gazettes that the Johnstone Shire Council had a specific By-law relating to the construction of fire proof buildings, the

minutes of Council dated 17 June 1925 says that "in future all applications be advised that the Act must be strictly complied

with" and on 18 August 1926 that "… reply be sent [to the Salvation Army] enclosing a copy of the Act with regard to

buildings in the First Class Area".45 No mention was made of By-laws!

A further search of the Queensland Government Gazette for

1925 did not show that the Johnstone Shire Council applied for an amendment to their By–laws to include a specific law

controlling the type of construction material to be used in buildings in Innisfail. Based on a lack of evidence to the contrary

it would appear that the Council used the declaration of a "First Class Area’ and the building constraints in that declaration

to guide the planning approvals for the town, rather than a special By-law.

THE

DEVELOPMENT OF CONCRETE TECHNOLOGY

By 1926 there were a number of significant new concrete

buildings in Innisfail including the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney building in Edith Street, the Park Hotel and the

Crown Hotel.46 The use of concrete in the reconstruction of Innisfail from the early 1920s reflected the growth of the use

of concrete across Australia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The use of concrete evolved over many centuries. The oldest

concrete discovered so far dates from about 5600 BC and was found on the banks of the Danube River at Lepenski Vir in Yugoslavia.

This early concrete was used to make hut floors in part of a village constructed by Stone Age hunter – fishermen.47

By 5000BC the art of making concrete appears to have died

out. It re-emerged in about 2500 BC when a form of concrete was used in the Great Pyramid at Giza in Egypt about 2500 BC.

Some believe that it was lime concrete while others believe the cementing material was made from burnt gypsum.48

The art of making concrete eventually spread from Egypt

to the eastern Mediterranean and by 500BC was being used in Ancient Greece. The Greeks used a lime based concrete to cover

walls of unburnt brick. This ‘pseudo concrete’ preceded real concrete and was composed of roughly broken stone

held together in a mortar of lime and sand. 49

It is possible that the Romans copied the idea of concrete

making from the Greeks. Early Roman concrete, dating from 300 BC has been found. The Roman concrete, made of a pink, sand

like material from Pozzuoli and lime, was a much stronger material than previously produced. 50

This discovery had a far reaching effect on building and

engineering during the next 400 years. It was not a combination of sand and lime as first thought, but a fine volcanic ash

containing silica and alumina which, combined with lime produced what became known as pozzolanic cement. One of the first,

large scale uses of pozzolanic cement was in the theatre at Pompeii, constructed in 75 BC.51

Interestingly, the Romans attempted to reinforce some of

their structures with bronze strips and rods. However, the process was not successful because bronze has a higher rate of

thermal expansion than concrete and causes spalling and cracking. Today’s steel reinforcing has the same rate of expansion

and contraction as concrete over the range of normal temperatures. 52

By the first century AD concrete had become accepted as

a structural material. However, with the decline of the Roman Empire most knowledge gained from the use of concrete seems

to have disappeared. 53

It is thought that the Normans re introduced the art of

concrete making; however, discovery of three Saxon concrete mixers dating from 700 AD in Northampton shows the process was

being used prior to the arrival of the Normans. The Saxons used a local aggregate, limestone and burnt lime as the binding

agent. 54

However, the Normans introduced concrete usage on a large

scale not unlike that of the Romans: concrete was used as infill material in walls that were faced with stonework. Concrete

was often used in foundations of churches, castles and of particular note in the White Tower of the Tower of London. However,

very little concrete was used in Medieval and renaissance periods.55

By the middle of the 18th century there was yet another

interest in the use of cement. In 1750 William Champion, manufacturer of brass, copper and zinc built a large mansion near

Bristol and built a giant concrete statue of Neptune in the middle of a lake in the grounds.56

In 1756, John Smeaton, an engineer of Leeds was commissioned

to build a lighthouse on the Eddystone Rocks in the English Channel. Two previous timber lighthouses had been destroyed in

storms. The new lighthouse needed to be very strong to withstand coastal conditions so Smeaton built it of stone bound by

a water proof lime mortar made of limestone manufactured using clay. Smeaton, after much investigation, used a mixture of

burnt limestone from South Wales and an Italian pozzolana from Civitavecchia. When the two were combined a cement was produced

that set under water. Thus, John Smeaton produced the first good quality cement since Roman times. 57

Towards the end of the 18th century there was a considerable

revival in interest in developing new types of concrete.58

On 24 October 1824 Joseph Aspdin took out a patient for

the manufacture of Portland cement. The name was derived from Aspdin’s belief that his mixture looked like Portland

stone was not because it was made in Portland. This cement was the most superior cement made to that time. He probably saw

his cement more as an external grade plaster to be used as brick render, thus producing a relatively cheap finish with the

look of Portland stone blocks.59

The first Portland cement works were established at Kirkgate

in Wakefield between 1826–1828. Soon after the Aspdin family expanded the business to London where a cement works was

constructed at Rotherhithe where Portland cement was used to repair, rebuild and reline the Thames Tunnel after it collapsed

during construction.60 This was the first major engineering works where Portland cement was used as a construction material.61

By 1847 another Aspdin cement works was established at

Northfleet. Here Joseph’s son William encouraged the use of concrete in house construction by building Portland Hall

in Kent. 62 However, despite the expansion of the use of concrete and the opening of a Aspdin Portland cement works in Germany

in 1860, the manufacture of cement was constrained by the cost of production. These excessive costs were overcome with the

introduction of the continuous process rotary cement kiln which was designed and installed in cement works at Hitch in Hertfordshire

in the 1880s.63

THE ADVENT OF REINFORCED CONCRETE 1848 - 1897

Possibly because the Romans had experimented unsuccessfully

with reinforce concrete using bronze rods the idea of reinforced concrete was not explored again until 1830 when it was suggested

that iron tie rods be imbedded in concrete to form a roof and again in 1848 considerable interest was shown in the construction

of the first reinforced concrete boat which was built in France.64

In a major step forward in 1854 Newcastle (England) builder

William Wilkinson applied for a patent for "Improvement in the construction of fireproof dwellings, warehouses, other buildings

and parts of the same". 65 Wilkinson’s patent proposed that iron ropes be embedded in fresh concrete with the ends splayed

out when the concrete was under load. The iron ropes were to follow the line of tension rising to the upper part of the beam

where it passes over the supports and falling to the lower part of the beam mid span. Wilkinson obviously understood the basic

structural principles and he rightly became known as the inventor of modern day reinforced concrete.66

The surprising thing about the development of reinforced

concrete in the mid to late 19th century is that, although its use increased considerably, its use did not develop from one

place. It seems to have been adopted in different places by independent and innovative builders.67

The use of concrete in Australia dates from the first

days of settlement. While Arthur Phillip brought a small amount of lime from England he needed much more to establish the

major buildings in the new settlement. The first lime was made from shell but even then there was not enough and the Governor

had to resort to the construction of buildings using inferior materials until material was found to make brick.68

However, good lime was found on Norfolk Island and in Van

Diemen’s Land in 1804 and in 1839 rock lime was being exported to Sydney from Point Nepean in Victoria. The availability

of good rock lime in Victoria and the lack of imported hydraulic lime meant that, unlike Sydney, Melbourne developed a stucco

architecture of a style no longer being used in Britain where hydraulic lime was being used. During the 1840s, apart from

civic buildings, a number of homes were constructed of crude concrete in Melbourne and in Adelaide during the 1860s.69 However,

as in Britain, concrete was much more widely used in foundations than in complete buildings.70 The first lime was burnt in

bush kilns with the rock lime and fuel stacked in layers. However, in major construction areas permanent kilns were quickly

constructed. These were in the form of inverted cones and were usually built into a cliff face or slope to reduce the amount

of construction required. As local production improved by the middle to the 19th century the importation of hydraulic lime

from Britain and elsewhere was reduced. However, the importation of cement did not decrease. 71

In the latter half of the 19th century concrete began to

be seen as not just a low grade mass material but one capable of ornamental and structural use. Cast cement of various forms

was used to substitute for stone. It was used for garden ornaments, fountains and architectural features. In Victoria on of

the first local patents was taken out by Charles Mayes in 1854 for a form of hollow concrete building block, while a method

of making hollow concrete blocks mechanically was patented in 1857 and a form of breeze block in 186472. By 1870 GA and HA

Bartlett of Adelaide were advertising as agents for Drake’s Patent Concrete Building Company of London which produced

stone breakers and concrete mixing and building equipment. By 1880 the use of concrete was fairly readily accepted for flooring

but was only occasionally used in the construction of walls or completed buildings. However, concrete foundations and fireproof

floors were fairly standard.73

In 1888 John Sulman presented a paper to the Australian

Association for the Advancement of Science in which he discussed ways of making concrete constructions fire proof or at least

fire retardant. The major use of concrete in Australia, however, remained cosmetic rather than structural until the production

of substantial quantities of Portland cement. 74

Production of Portland cement began in Victoria in 1859

when GJ Knight tested newly discovered limestones in a small kiln and produced a small amount of hydraulic cement. A ‘shelly

or magnesian limestone used in combination with ironstone produced a form of cement patented by T P Edwards in 1862. The first

sustained attempt at artificial cement manufacture seems to have been made in South Australia75. William Lewis, a limeburner,

is said to have experimented for some years with mixtures of lime stone and clay producing a material which was said to be

"little inferior to Portland cement". Lewis opened his Marin Cement Works at Brighton in South Australia in December 1882.

This company struggled financially but a new cement works, constructed on the same site in 1892, used the same technology

to produce more than a million tones of Portland cement during the following sixty years.76

While Lewis was struggling in South Australian other manufacturers

sprang up in almost every colony. By 1889 R D Langley, an English expert was claiming to have made Portland cement in Brisbane

in 1889. Australian cement companies operated with mixed success because the industry was still somewhat primitive and it

was difficult to maintain consistent quality in the product. This became an issue with the rapid expansion of reinforced concrete

construction after 1900. During the next twenty five years the process of making cement went through a period of significant

technical development. The industry adapted milling machinery to pulverize stone and pugmills to mix the material. Early plants

used a wet process until shaft kilns were developed to produce dry cement. Technical development continued with the introduction

of rotary kilns in 1901.77

A number of cement companies were established but

the most successful was the Commonwealth Portland Cement Company which managed to establish markets throughout Australia.

The company controlled 45% of the Australian market just prior to the First World War. The importation of concrete virtually

ceased during the war leading to considerable expansion of the local industry, including the establishment of Darra Cement

in Brisbane in 1919, so that by 1925 the first draft Australian Standard Specification for Portland Cement was published and adopted in 1926 as Australian Standard A.2. By this date there were about

eleven concrete production companies operating in Australian.78

Innovation and experimentation was a feature of the cement

industry in Australia. Our distance from Europe and the multiplicity of our local manufacturers combined to give the industry

the ability to diversify and experiment. Some extraordinarily advanced experiments were the result particularly in the construction

of bridges and aqueducts. The first use of concrete in bridge construction was in foundations, piers and abutments and in

mass-concrete culverts. The first important concrete bridge was the Lamington Bridge over the Mary River at Maryborough in

Queensland which was constructed in 1896. It was designed by Alfred Brady on the system first developed in 1884 by the Hungarian

Robert Wunsch. Construction involved a series of wrought iron or steel frames set into the flat topped segmented concrete

arches of the bridge. Though the 24.2 metre span was slightly less that that of the Emperor Bridge at Sarajevo there were

eleven arches, so the bridge as a whole was very much bigger. It was the most substantial Wunsch Bridge outside Europe and

perhaps the most substantial in the world at the time79.

Other significant Queensland bridges included the original

bridge across the railway in Edward Street, Brisbane, next to Central Railway Station. It was built with mass concrete abutments.

It was designed by Queensland architect F D G Stanley in 1887 and built soon after. Similarly, the low level bridge over the

Herbert River at Gairloch, near Ingham, was designed about 1889 with concrete in the piers but not in the deck. This was surprising

because it was designed by A B Brady, who was a pioneer of early reinforced concrete design in Australia.80 The other significant

early use of concrete in Australia was by Queensland Railways in the construction of bridge piers such as the major steel

truss bridges of 1899 at Rockhampton and Macrossan near Charters Towers.81

By 1905 Melbourne engineers Monash and Anderson, agents

for the reinforced concrete system of construction, were building two concrete storage buildings for the Australian Mortgage

Land and Finance Company in Melbourne. A significant feature of these buildings was that they were constructed using monolithic

concrete frames. Later in 1905 Monash constructed two buildings in Olive Lane, Melbourne using American reinforced concrete

technology to create buildings without brick cladding. 82

Thus, while concrete production began in Victoria in 1859

Queensland enthusiastically utilised reinforced concrete in road and rail bridge abutment construction in the 1880s and was

meeting its supply needs with concrete from the Darra Company established in 1919. Engineers Monash and Anderson were using

reinforced concrete in Melbourne buildings by 1905 but it appears that the most significant use was the reconstruction of

the sugar towns of north Queensland in the 1920s and 1930s.

OTHER

INFLUENCES ON THE GROWTH OF INNISFAIL

Apart from Local Authority Acts and Council By laws there

were other, significant influences on the development of Innisfail during the 1920s and 1930s. Planned cities have existed

from ancient times. Often they followed a simple grid pattern laid on the landscape, with houses side by side along straight

streets. The first Innisfail town survey shows the town laid out in a similar grid pattern. While the town was initially built

along the Johnstone River frontage, the town centre shifted after flooding in 191383 when Rankin Street was established along

the spur of the hill above the river and Edith Street at right angles down the rear of the hill.

At a special meeting of Council in June 1920, the consultant

engineer from Brisbane Harding Frew advised that he had drawn up an unfinished Town Plan Scheme for Innisfail. The final plan,

which was about drainage and street formation, was tabled at a meeting later in 1920.84

As early as 1909 the Johnstone Shire Council was

active in implementing its powers under the Local Authority Act of 1902 and Amendments by establishing

recreational gardens and beautifying the town, by installing gas lighting and beginning the process of developing a town plan.

By the early 20th century town planning was developing as a profession in its own right and several schools of thought about

civic design became influential. They included the Garden City and City Beautiful movements.

Major redevelopment schemes for big cities around the world, including the planning of Canberra by Walter Burley Griffin and

his wife Marion Mahoney, were often based on these early town planning ideas. Creating beauty in towns and cities to inspire

civic pride led to the establishment of parks and recreational spaces for the use of the citizens.85

In 1933 the Queensland Department of Lands was following the trend

of creating parks and gardens by setting aside land in Innisfail for a botanical garden.86 In a news article in the Johnstone

River Advocate in 1934 titled "Civic Beautification for Innisfail", the Innisfail Publicity Association discussed with the

Council Works Committee what they hoped for the town. The Works Committee advised that work would start on improvements to

parks after a new engineer was appointed.87 Later in 1934 the Council had built garden plots in Rankin Street, established

botanical gardens near the railway station and planted palms at the station.88

By 1933 The Johnstone River Advocate was noting ‘Innisfail’s

Magnificent Outlook" with approximately ₤70,000 worth of cane lands in the district sold since the beginning of 1933.

Innisfail was described as the sugar capital of the Commonwealth.89 Articles in the Johnstone River Advocate during 1933 and

1934 described a range of major infrastructure development including the Hospital, Post Office, Swimming Baths, Water Scheme,

Manual Training Building at the State School, School of Arts Book Library, houses, shops & 50 new farms opened at Palmerston.

Thus, by the mid 1930s Innisfail had become a thriving town with

a substantial business centre, municipal infrastructure and recreation areas and parks. An ideal setting had been created

for the planning and vision which was to create the magnificent new Johnstone Shire Hall.

JOHNSTONE SHIRE

HALL - "A PICTURE PALACE"

The Johnstone Divisional Board had purchased land in Rankin Street

for a Divisional Board Office after October 1881. Two earlier offices, which had been built on the site, were destroyed by

fire. Unfortunately, on 21 December 1932, the third timber Johnstone Shire Hall in Rankin Street was also gutted by fire.

The destroyed building was a landmark in the centre of town. It appeared to be a large, building extending over two blocks

in an ‘L’ shape. The building had extensive awnings at the ground and first floor levels with an open verandah

on the ground floor.

Apart from it fulfilling the role of shire office, the hall had

been used for theatre productions and as a movie theatre. 1930s photos of the shire hall show the extensive building awnings

covered in movie theatre advertising for Tivoli Pictures and Screen News. Advertising at the northern end of the building

indicated that there was a hall on the first floor.

The intensive use of the shire hall as a place of entertainment,

particularly movie entertainment, may have influenced the design of the new building after the fire in December 1932. The

facade of the 1935-38 shire hall, [present Johnstone Shire Hall], viewed from the north along Rankin Street, gives the impression

of an Art Deco picture theatre.90 While no evidence has been found to substantiate this theory, the use of the former shire

hall as a place of entertainment and the large spread of movie theatre advertising on awnings could give weight to the idea.

Council debate during the development of building plans for the new hall also adds weight to the idea of the development of

design for a shire hall facade reminiscent of an Art Deco picture theatre.91

While Council meeting minutes don’t allude to any specific

design for the new hall, the loss of the old shire hall in 1932 as a venue for entertainment was obviously important because

at its meeting on 9 June 1933 Councillors commented on the need for a hall in the new building. Innisfail was "…een

as the worst place in north Queensland for halls [for entertainment]." 92 Council also wrote to Amalgamated Pictures Ltd,

the lessees of the old hall for movies on a Saturday night, saying that "it is our intention to rebuild the…unicipal

buildings immediately we are able.93

Moving swiftly after the fire Council appointed Townsville architectural

firm Hunt and Hunt to draw up plans and estimates for a new building on the same site in Rankin Street. The new building was

to consist of a hall on the lower level, basement, council chambers and public offices and it was to have "ample ventilation".94

The Council accepted the plans drawn up by Hunt and Hunt and voted

to seek a Treasury loan and subsidies worth ₤8,000. The loan and subsidy together with the £4,000 insurance money would

meet the cost of the new building. Once confirmation of the loan was received the plans were to be submitted to the Department

of Public Works for approval.95

In March 1933 the State Government advised Council that the plans

for a new shire hall were not compliant with sections of the Local Authorities Act and would "not be for the benefit

of a particular part of the shire."96 .

The following month saw a new Council in office with a make up

of 5 Labor councillors and three from the Ratepayers Association which supported the returning Mayor S K Page. Councillor

Crowley (Labor), who had been a loud opponent of the Hunt design for the Shire Hall and of the fact that Council had not called

tenders to select an architect, was elected to the newly formed Finance Committee. Crowley asked that the Committee investigate

the non compliance and present a report at a special meeting.97

While the report to the Finance Committee on the non compliance

of the plans prepared by Townsville firm Hunt & Hunt in March 1933 has not been located it would appear that the plans,

drawn up at the direction of the Johnstone Shire Council, did not address the need for a building suitable for the climate.

It would also appear that sections of the community, particularly the councillors representing the outlying wards, were resentful

that so much money was being spent on a building they felt would be of little use to their constituents.98

The minutes of the Finance Committee dated 21 June 1933 indicate

that the new plans paid more attention to the need for high ceilings, verandahs, large meeting rooms, a large hall for the

use of the community and "ventilation [which was] to be the first consideration throughout the building".99

At this time the depression was beginning to wane and, although

the cane industry had cushioned the effect the depression on the Innisfail district, the Council was in serious debt because

of unpaid rates. On 29 March 1933, although the Council had reduced the general rate from 8 ½ pence to 7 pence, it was still

owed ₤22,000 by the end of 1933.100

The election of a Labor dominated Innisfail Council followed the

election of a State Labor Government under William Forgan Smith in 1932. A major platform of the newly elected government

was the initiation of long term development projects101 to ease widespread unemployment. The government set up the Bureau

of Industry to promote public works and the Unemployment Relief Fund to facilitate these works through the use of relief labour.102

With over 32,000 registered unemployed when Forgan Smith came to power the major objective "…as to get the men back

to work." With 18% unemployment in 1932 the Forgan Smith Government did well to reduce the rate to 9.13% in 1934 which was

the lowest unemployment rate in Australia at that time.103

By March 1933 the Johnstone Shire Council had applied for and

received a loan of £46,000 for a water scheme for the town and £25,500 in subsidised loans for other works.104 There is probably

little doubt that the State government supported labor initiatives at a local level in Innisfail.105 It is interesting to

note that, at the time, the local member for Herbert, Percy Pease, held office in State Cabinet as Secretary for Public Lands

and was Acting Premier from time to time.

In May 1933 Council was discussing the option of asking the Dept

of Public Works to draw up new plans for the building. These plans would have to meet the needs of the community. Evidence

of the community’s interest in the new shire hall and concern that the building would provide for the needs of the community

was obvious in a meeting called by the Ratepayers Association and other bodies on Friday 9 June 1933. The meeting discussed

the shortcomings of the old design and asked that the new building "be a place which will be an acquisition to the town".106

A sub committee was established from the meeting to confer with

the Council Works Committee. The sub committee would inform the Council of the wishes of the community with regard to the

new hall. 107

By March 1934 Treasury was asking if Council planned to go ahead

with the construction of a new shire hall. Council advised that they had approached the Dept of Public Works to draft plans

and specifications and by April 1934 the department advised that some work had begun on preliminary sketch plans for the new

building.108

By then, however, Council had more pressing matters to consider.

At the request of the Johnstone Shire Council, the Home Secretary, E M Hanlon, had called for an investigation into the shire’s

finances and, as a result, the Shire Clerk, J B Perrier, was suspended from office on 3 March 1934. A Cairns accountancy firm,

appointed to investigate, found six major areas of concern including poor management by the shire clerk, high administration

costs, that the reduction in the general rate in 1933 was unnecessary, and the poor rate of referral of relief workers to

the Department of Labour.109

Despite the Council’s difficulties the community was asking

if the new hall would be built in time to celebrate Innisfail’s centenary. 110 However, community debate continued particularly

when the plans, drawn up by the Department of Public Works, were estimated to cost £25,000. Chairman S K Page wanted a vote

from the people on the matter "…t seems a lot when the district needed roads and footpaths." Councillor A F Marty (Labor)

said that Council needed to look to the future to provide a monument worthy of Innisfail and the district. Further community

support was expressed in a Johnstone River Advocate editorial which said that the Council should be congratulated on its majority

vote to secure a shire hall. "The future of Innisfail is of such a magnificent character that it requires the adoption of

a broad vision. The Shire Hall should be a building worthy of the town and its district."111

A decision to construct the building was dependent on Treasury

approval to supply loan and subsidy funds. Councillor Crowley pointed out that the local Labor Party supported the construction

of the hall because it would provide work for local unemployed. He said that because the plans had the backing of Percy Pease,

local Labor member and Secretary for Lands, the approval of funding by Treasury was "all but settled."112

Six months later Percy Pease announced that funding had been granted

by Treasury and that the project funding had been approved expressly to relieve unemployment. Chairman Page immediately pointed

out that he thought that skilled men would be required to do most of the work.113 These words were to be prophetic because

the cost of the project was to blow out towards the end because of the need to use skilled tradesmen to finish off the building.

Local support for Council’s decision to proceed was expressed

in letters to the editor and a letter from the local eisteddfod committee which said that "Council is to be congratulated…[for]

deciding to build a hall that will be a credit to the town."114

The cost of the building continued to escalate when, in October

1934 Council announced that the cost would now be in the vicinity of £36,830. Debate in Council was heated and Chairman S

K Page continued to express his opposition to the building. Page was overruled and a telegram was sent to Treasury asking

that a loan and subsidy of £11,830 be added to the already promised £25,000. Percy Pease advised by letter on 28 October 1934

that a full loan (no subsidy) of £11,830 was approved by Treasury.115

However, rumours that the Department of Public Works could not

supply plans and specifications, were confirmed when Council advertised on 21 June 1935 for an architect to submit plans for

Council inspection. Seven expressions of interest were received from JJ Rooney and CD Lynch of Townsville, G Osbaldiston,

Hill and Taylor of Cairns and ABC Dyer wrote asking for further information. Messrs Hill and Taylor, Cairns, SG Barnes, Cairns

and BM Brown of Atherton were short listed with Hill and Taylor of Cairns appointed as Architects for the new Shire Hall on

8 July 1935.116 Within ten days an advertisement seeking a construction foreman was placed. Wilhelm (Bill) Van Leeuwen, a

builder and contractor of Innisfail was appointed.117

Debate continued in Council and in the community for and against

the project mostly because of the cost. Councillor Page remained bitter over the acceptance of new loan funds. In November

he said that the Day Labour Employment Scheme would prove expensive, that plans were not available, that the construction

foreman, who was to receive 8% of the cost of the building, would now receive a greater benefit than was identified at the

point of his employment.118

A petition was sent by the Ratepayers Association to the Premier,

W Forgan Smith, the Secretary of Public Lands, Percy Pease and the Secretary of Public Works, H A Bruce requesting that a

public poll be taken on the question of loan monies but E M Hanlon, Secretary for Health and Home Affairs refused this request.

The refusal may have been related to a letter sent from the Council saying that the building was well designed, would not

be a burden to ratepayers, that the local Labor Party supported the project and that the Ratepayers Association comprised

six members who could not muster a quorum at the last annual general meeting.119 It is also useful to know that most members

of the Ratepayers Association were from the El Arish and Silkwood area which had previously been a separate division from

Innisfail and people from the area resented so much money being spent on a building they felt they had no use for.

Despite the debate in Council a notice was published on 15 November

1935 advising that work had commenced on construction of the Shire Hall.120 On 22 November the Johnstone River Advocate carried

a full page story on the new building detailing the cost and size and giving a description and drawings. This was the first

opportunity that the Innisfail community had been given to see the proposed building.121 In early January about twenty five

men were working on the building and tenders had been called for the supply of 140 tons of fabricated structural steel.122

The first hint that the cost of the building was going to blow

out again came when Mr Pease advised that Council could employ full time workers when the relief workers’ time ran out

and by October 1936 thirty one men were employed on the building.123

During 1936 Local Government elections took place. Four labor

party members were elected along with four farmers’ representatives, three independents and Councillor S K Page representing

the Ratepayers Association.124

The question of the cost of the Shire Hall was a dominant feature

in Council deliberations during 1936 and concerns were being expressed in the press about these costs. An optimistic report

advised that the walls and piers were nearly to the first floor level and that the building would be ready for roofing at

the end of January 1937, the ground floor ready for use in April and the first floor by July 1937.125

Unfortunately, by April 1937 increasing costs forced Council to

apply to increase the loan to £45,000 stating that increased cost for labour to build the form work was the cause.126 Treasury

responded expressing concern because the cost of the building was now 80% over the original estimate. Council replied that

a good deal of the increase was caused by demands from the Department of Public Works including the early use of "day labour"

when the project required skilled tradesmen. The estimation of cost was based on the use of day labour which was no longer

feasible. A further impact was the increase in wages as the depression eased.127

By 1938 the Forgan Smith Labor Government had begun to recognize

the shortcomings of the Labour Relief Scheme and introduced a program of public works which would generate full time work.

This work was to be funded under the State Development Tax Program. Some of the major projects started during this period

were the Story Bridge in Brisbane, Queensland University and Mackay Harbour. Unfortunately for the Johnstone Shire Council

the change of attitude towards employment of long term labour came too late for there to be an impact on the rising cost of

construction of the Shire Hall.128

Sadly, in May 1937 Bill Van Leeuwen, the Construction Foreman,

was seriously injured on the Shire Hall site when a large metal beam fell on him. He was sent to Brisbane and later returned

to Innisfail where he died towards the end of the year. Bill’s brother Peter assumed the role of Construction Foreman

after Bill was injured. 129

By December 1937 the cost of the building had risen to £52,000

with the cost of plastering exceeding the estimate by 150% after tradesmen on the job applied for a wage increase.130

During the latter part of 1937 construction moved quickly and

in September the traditional flag was flown when external construction was completed. By then the roof was on, down pipes

in position, the first coat of plastering nearly completed, laying of the flooring on the first floor had started and the

framed windows and roller shutters were fixed in position.131

In November 1937, GH Bromhall, former State Manager of the Queensland

National Bank was visiting the town and wrote to the newspaper to praise Innisfail for the progress evident there. He spoke

of new roads and new public buildings although another writer to the Advocate complained of the state of the roads at the

same time. Another complaint was published in Frank Clune’s 1938 travel book Free and Easy Land, that the shire

hall was "bigger than Sydney Town Hall, a tremendous, pretentious, hideous structure of concrete with iron balconies."132

While visitors were commenting on the building the Management

Committee was busy selecting tenders for furniture, and the Shire Clerk reported that the ground floor was nearly ready for

occupation. Tenders for letting offices were placed and the long awaited announcement came that the removal to the new Council

offices would commence on Tuesday 4 January 1938. After five years of operating from temporary premises the Councils business

was to operate from its own premises in Rankin Street.133

The first meeting of Council in the new building took place on

20 January 1938.134

Minor completion work was continuing on the structure including

plastering, painting and panelling. The widening of the central doorway into the vestibule by one foot on either side cost

£21/15/-. Included in the finishing touches was the matter of the vestibule tiling. In the original Hill and Taylor specifications

it had been intended that the front entrance would feature terrazzo flooring. When the cost of the building spiralled in 1937

Council asked the Shire Engineer to investigate suitable tiling. In January 1938 tiles by S Messaglia of Ingham were chosen.

The tiles themselves were produced on a machine which had originally been brought to Innisfail in the 1920s by Charlie Vecchia

and Domenico Beccaris and later sold to Messaglia.135

The Johnstone Shire Hall was officially opened on 1 July 1938

with speeches and toasts at 3.30pm. Civic dignitaries from throughout the region attended. Mrs Edgar Young, the daughter of

Sub Inspector Robert Johnstone, explorer of the Johnstone River, cut the ribbon to open the building. Mr T H Fitzgerald, a

member of the family of the first settler, Thomas Henry Fitzgerald, was also present.136

An evening of entertainment followed with dancing, euchre and

bridge enjoyed by 1200 people. The night raised £164 for the Ambulance Centre.137

Within a few months of opening reviews and advertisements appeared

in the Advocate for a range of functions in the Shire Hall. These included a vaudeville show by the Stanley McKay Touring

Group, a public lecture by Count von Luckner telling "How he ran the Blockade during the War in a Windjammer", a mannequin

parade arranged by the Innisfail Branch of the Catholic Daughters of Australia and a fancy dress ball for children organized

by the Innisfail Convent School.138 A significant major boxing event was arranged towards the end of the year. The remnants

of a boxing ring used for warming up and training can be found on the lower floor of the building.139

In October 1938 it was reported that the final touches to the

plastering and tiling of the vestibule were practically completed. The final cost was reported to be £54,725.

In the years following a variety of community functions featured

in the hall with it’s ‘hey day’ perhaps being the Saturday night dances during the 1950s and 60s. Today

the building is mostly used as the Johnstone Shire Office. The first floor hall has been used since its construction, for

the North Queensland Eisteddfod at May Day each year.

Plans are in place to hold a major celebration in 2008 to celebrate

the seventieth anniversary of the Shire Hall.

The magnificent Johnstone Shire Hall is probably significant as

the only 1930s art deco reinforced concrete municipal building of its style and scale in Queensland. A survey of the Queensland

Heritage Register and the Architects and Builders Journal shows that towns in Queensland such as Brisbane, Rockhampton,

Townsville, Toowoomba and Cairns can trace the major building booms in their towns to the pastoral boom of the 1880s and into

the early twentieth century. Buildings such as the Rockhampton Supreme Court building (1886-87), Toowoomba City Hall (1900),

Brisbane City Hall (1920 – 1930), Maryborough Town Hall (1908), Sandgate Town Hall (1911-12) were all constructed in

masonry, brick and stone. Most bank buildings were constructed of similar materials including the Rockhampton Commonwealth

bank (1915), the Cairns Court House (1919-21).

Research to date has not identified any municipal buildings of

reinforced concrete of a similar scale and design to that of the Johnstone Shire Hall. It is a rare and important example

of its type in Queensland.

THE ARCHITECTS

AND BUILDERS OF THE JOHNSTONE SHIRE HALL

The Johnstone Shire Hall was constructed between 1935 and 1938

in the part of Innisfail declared a ‘First Class Area’ in 1925. The building was constructed to a design by Cairns

architects Hill and Taylor and the construction supervised by Wilhelm (Bill) Van Leeuwen and his brother Peter. Hill and Taylor

were significant architects in north and far north Queensland between the First and Second World Wars. The Van Leeuwen Brothers

were also significant for their construction work across all of Queensland but particularly in north Queensland.

It is known that the Archictects Hill and Taylor and the Van Leeuwen

Brothers collaborated on a number of buildings including the National Bank in Cairns, the Hotel Grand Central and the Johnstone

Shire Hall. Mrs Wilma Erie, daughter of Peter Van Leeuwen, believes that the Van Leeuwens worked on a number of other buildings

with Hill and Taylor.140 While the Van Leeuwen Brothers worked in timber and all other construction material their most significant

contribution were the reinforced concrete buildings they constructed throughout north Queensland but particularly in Innisfail.

Between 1932 and 1936 the Architects and Builders Journal identified

12 significant buildings designed by Hill and Taylor. These buildings included the Cairns Masonic Temple in 1934-35, the Cairns

Golf Club in 1934, the Johnstone Shire Hall from 1935 to 1938, the Hotel Grand Central in Innisfail in 1935 and the New Federal

Hotel and shops in Cairns in 1936. At the same time the Van Leeuwen Brothers were busy building most of the significant buildings

constructed in Innisfail including the National Bank, Hotel Grand Central in collaboration with Hill and Taylor, the Queens

Hotel, the Bank of NSW, the Commonwealth Bank and the Commercial Bank of Sydney.141

SUMMARY

Johnston Shire Hall is an important building in Innisfail and

north Queensland. It was constructed at a time of relative prosperity for the district because of the expanding sugar industry.

The building was funded using government incentives such as loans and subsidies which the Queensland government had introduced

to encourage major project construction during the 1930s depression. However, construction was hampered by political interference

and by disputes in Council over building plans, size of the building and use of day labour during construction. Despite these

problems the building was a triumph for the architects Hill and Taylor of Cairns and Innisfail builders Wilhelm and Peter

Van Leeuwen. While the design of the building was not technically significant its size, scale, construction in reinforced

concrete and art deco façade created an imposing shire hall which has remained an icon of the Innisfail district for seventy

years. Despite some criticism the community was generally delighted with the building and expressed that delight in the Johnstone

River Advocate through letters and articles praising the Council for the decision to construct a building which was a credit

to the district. The building, which has filled the need for a large hall, has lived up to the hopes and dreams of the Johnstone

Shire Council and the Innisfail community by becoming a focal point of community activity and Council administration.

THE PHYSICAL

EVIDENCE

The Johnstone Shire Hall is in good condition. The building is

also remarkably little changed from 1938. While the lower levels have been modified, the main level and the auditorium or

hall survive largely as the architects intended in plan and detail.

Some of those changes have been reversed as part of the recent

repair and reconstruction work.

DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE

Council holds a full copy of the construction drawings prepared

by architects Hill and Taylor between 1935 and 1938 together with drawings prepared by Cleland Robinson Architects Pty Ltd

in 1983 apparently as part of a proposal to alter the building at that time.

By comparison relatively few photographs of the building exist

of its construction or immediate post construction phase.

Council minutes and records of the period in which the building

was constructed have been searched but more recent records that might indicate more precisely information about later changes

have not.

The early drawings are a useful resource in determining those

changes that have taken place since 1938. In examining the building fabric it is clear too that aspects of the building were

not built as documented. For example there is no evidence in the tiling of the foyer of the iron screen shown on the drawings.

The foyer ticket box by contrast is thought to be contemporary with the foyer tiling but does not show on any drawing.

Some relatively minor contradictions such as the position of stairs

between levels is apparent and there is some doubt that the caretaker’s accommodation was ever constructed.

THE BUILDING

FABRIC

The Johnstone Shire Hall is remarkable in the extent to which

early building fabric survives. Designed as a steel frame and clad in concrete with infill walls also in concrete or masonry

the building is one in which structural engineering has, to a large degree, influenced the design.

A ‘ring’ of concrete at both levels surrounds the

more conventional timber framed floor and plaster clad partitions within it. That ‘ring’ is an essential part

of the structure of the building providing rigidity or bracing in the horizontal place in the way that concrete wall panels

provide bracing in the vertical place.

The steel framed windows and roller shutters to the upper floor

are more substantial than perhaps the more common timber framed fenestration and are more resistant to fire.

Memories of the 1919 cyclone and of course the fire that destroyed

this buildings predecessor must have been uppermost in the architects minds or indeed formed part of the brief for this important

building.

In plan the building is also unconventional when compared to other

town halls in Queensland or even the buildings of this scale in Innisfail.

The concrete verandahs that surround both levels are seen as secondary

spaces providing protection to the main walls against rain and wind. While used occasionally as circulation (and especially

to access the offices at the lower level) they do not form part of the calculated net floor area at either of the primary

levels.

At the first basement offices have been created in an area designated

in the architect’s plans as caretaker accommodation. That work is crudely executed in lightly framed and clad walls.

This area, presently occupied by engineering services and planning has been poorly planned. It is in all respects a secondary

standard.

Toward Rankin Street at this level an early gymnasium exists.

The space has most recently been occupied by the State Emergency Service. Again the work is clearly later than the main building.

A further section of this level has recently been floored and is providing space at present for Council archives.

At the lowest level doors provide access for vehicles. The ground

surface has been concreted. Air handling plant is located at this level.

At the main or council office level verandahs accommodate later

air conditioning riser ducts and distribution. Within the habitable space some changes have taken place. Early rooms have

been removed and modern office partitioning installed to create new offices. Some additional doors have been made in existing

rooms and an additional safe or strong room created. Toward the rear of the building at this level more original fabric survives.

While some further subdivision of rooms is evident so too is evidence of walls removed to create larger spaces. Early toilets

in this area have been modified but much early fabric survives.

Toward Rankin Street at this level change is more dramatic. Early